Man on a cell phone in Ghana. Photo by Arne Hoel via The World Bank.

As Ghana prepares for presidential elections in 2020, about 75 percent of the population access the internet via mobile phones.

On October 1, 2019, when the government’s proposed increase in Communication Service Tax (CST) took effect, Ghanaians took to Twitter with the hashtag #SaveOurData to demonstrate their displeasure — directing their rage mostly toward Ghana’s telcos as well as the government.

The tax was proposed as an upfront deduction on the purchase of any prepaid card as well as any other electronic communication services including the cost of internet data and SMS. This also means consumers are taxed whether they use a particular communication service or not. For example, the CST charge is pre-taxed on providing communication services such as SMS, calls, internet, etc to subscribers before they actually use these services.

This extreme surge in internet data costs will inevitably exclude those who can’t afford data and therefore can not participate in political debate and dialogue on social media and mobile platforms.

Many tweets from the ongoing #SaveOurData online protest accuse Ghanaian telcos for being the mastermind behind the recent exorbitant data charges. However, the increase in data prices is a result of the government’s increase in the CST from 6 percent to 9 percent. Previously, the CST tax was paid by the telecommunications companies, however it is now paid by users in full since the increase took effect in October.

The lead convener of the online protest, Saddick Adams, an award-winning sports journalist in Ghana, tweeted:

Dear Valued Telcos,

We in #SaveOurData campaign are NOT protesting “Unusual Technical Challenges”.

We are fighting CONSISTENT excessive charges. We are calling for a drastic reduction in anti-poor data prices. An end to exploitation of market power and reckless service

The #SaveOurData campaign group awaits approval from the Ghana Police Service to protest against the high data charges and promises to march to the Ministry of Communication and telecom offices:

#SaveOurData is trending and I assure it will not end here on Twitter. We are walking to the Communications Ministry and all the Telcos soon.

We are not angry enough

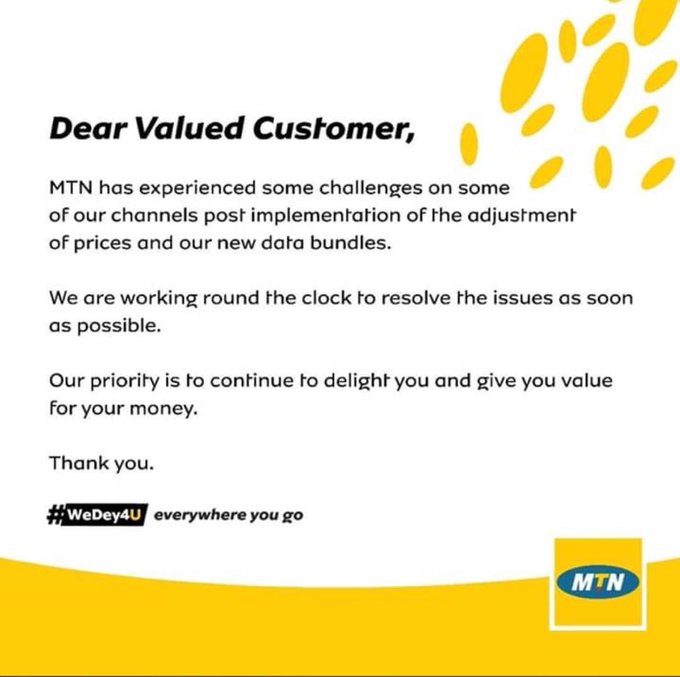

The telecoms company, MTN Ghana Limited, in particular, has been accused of ripping off ordinary Ghanaians of their meager income with high data charges, and their reputation has been shattered by the online protest:

Nathanial Obeng (@obengnat), a journalist, and marketer, tweeted:

Dear @MTNGhana , our plea is not about your one day technical fault but rather how expensive data has become in the country.@ameyaw112 @SaddickAdams #SaveOurData

Nungua Mia Khalifa (@BlackDelite) also accused MTN Ghana of robbing Ghanaians with their high data charges:

Dear @MTNGhana,

Your network is big across Africa.

You are the biggest running mobile money network.

The largest network usage in Ghana.

What at all again do you want that you keep robbing us of the little cash we raise from our hustles?#SaveOurData

Social media in 2020 elections

Social media during elections in Ghana plays a critical role in convincing voters and disseminating political messages. It directly impacts how voters make their final decision, helps hold leaders accountable and encourages greater and more informed participation. An active social media presence further boosts voter turnout, empowers political activists, and strengthens certain previously marginalized voices.

Internet shutdowns are common during elections in a number of countries around the world, especially in Africa. A few months prior to the December 2016 elections in Ghana, the Inspector General of Police, Ghana, indicated that the government was considering limiting access to social media networks to prevent and control the spread of fake news and misinformation and to maintain peace. But a more subtle way of disrupting service is to increase taxes on data to prevent citizens from participating in national and political online discourse.

The recent spike in internet data charges will likely reduce the number of people who engage in political discourse via social media platforms during the election period in Ghana.

A recent report published in November 2019 by the University of Exeter provides an overview of the mixed impact of social media on politics in Ghana:

The fact that elections – from party nominations to presidential and parliamentary contests –

are often extremely closely fought also means that, while a politician cannot rely on social media alone, an efective use of platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp can help to

make the difference between winning and losing. Given the (perceived) importance of social media to politics, there is heavy investment in this space.

A significant majority of journalists interviewed for this report estimated that over 80 percent of their leads for stories aired or radio and TV were sourced from social media.

Unsurprisingly, the incumbent government hired over 700 “social media communicators” to amplify their party message on several social media platforms. They were paid small allowances and given phone credit to disseminate propaganda messages and respond to political opponents. In an interview captured in the University of Exeter report, with one of the ruling party’s communicators, pointed out how they used social media to “magnify” the little mistakes of their political opponents to win the 2016 elections:

“Because [the NDC] couldn’t use social media effectively, they did some projects

but it looked as if they did nothing […] When we noticed a little mistake from them, it was

what we hyped on social media. We used [social media] extensively and it contributed

about 40% to our victory.”

The increased CST will exacerbate inequalities in representation and voice. Groups such as rural women, citizens with little or no formal education and others who cannot afford smartphones or mobile phone credit, are vulnerable to exclusion.

Customers bear the burden

According to the government, the increased income from CST aims to strengthen cybersecurity, protect users of information technology and combat money laundering, among other financial crimes.

This CST tax increase from 6 percent to 9 percent is levied on charges payable by a user of an electronic communication service provided by the telecom operators.

Currently, Ghanaian mobile users are subject to pay several taxes (value-added tax-VAT, national health insurance levy-NHIL and an additional CST of 9 percent) on services such as calls, SMS, and data usage.

Historically, an amendment by the government to increase CST is always aimed at pushing telecoms in Ghana to pay more taxes. However, that additional tax burden is always passed on to the consumer by the telecommunications companies.

Therefore, it was not surprising that the Ghana Chamber of Telecommunications issued a statement indicating that the increase CST will be “borne by the customer:”

CST, as specified in Act 998, is a consumer tax and will thus have to be borne by consumers. This will require modifications of what customers pay in total for communication services. As intended, the incidence of the modification will thus be on consumers. It will increase the cost of telecommunication services.

In Ghana, young, affluent and educated people are more likely to have access to the internet — which creates a huge gap. The high cost of data keeps many citizens offline —, especially women.

One gigabyte (GB) of internet data in Ghana costs the equivalent of $3.60 United States Dollars, which is more than 2 percent of the monthly average income. It certainly does not meet the United Nations’ “1 for 2″ threshold for internet affordability.

The online protests led the government to ensure telcos stop upfront deductions – calls, SMS, internet data, etc, but the CST is still in place and has not been eliminated by the government.

Bright Simons, a long-time consumer rights activist argues in his recent blog post that “jacking up CST rates, as the government has been doing recently, however, is clearly and painfully contributing directly to the falling value of data and voice vouchers that consumers all over Ghana keep lamenting about.”

Digital inclusion at stake

A report by Deloitte indicates that eliminating CST on mobile data and halving it to about 3 percent on other services such as calls and SMS reduces barriers to mobile usage and promotes digital inclusion.

Savings from CST all together will be passed to consumers and create an additional 1.3 million connections to the internet.

It would also increase productivity by up to 0.5 percent, generate over $200 million USD in additional investments in 2020 and increase economic growth.

The increased CST creates a huge barrier to affordability and compounds existing digital inequalities disproportionately felt in rural areas and among women, the elderly and citizens with little or no formal education.

News, Politics , Sports, Business, Entertainment, World,Lifestyle, Technology , Tourism, Gh Songs | News, Politics , Sports, Business, Entertainment, World,Lifestyle, Technology , Tourism, Gh Songs |

News, Politics , Sports, Business, Entertainment, World,Lifestyle, Technology , Tourism, Gh Songs | News, Politics , Sports, Business, Entertainment, World,Lifestyle, Technology , Tourism, Gh Songs |